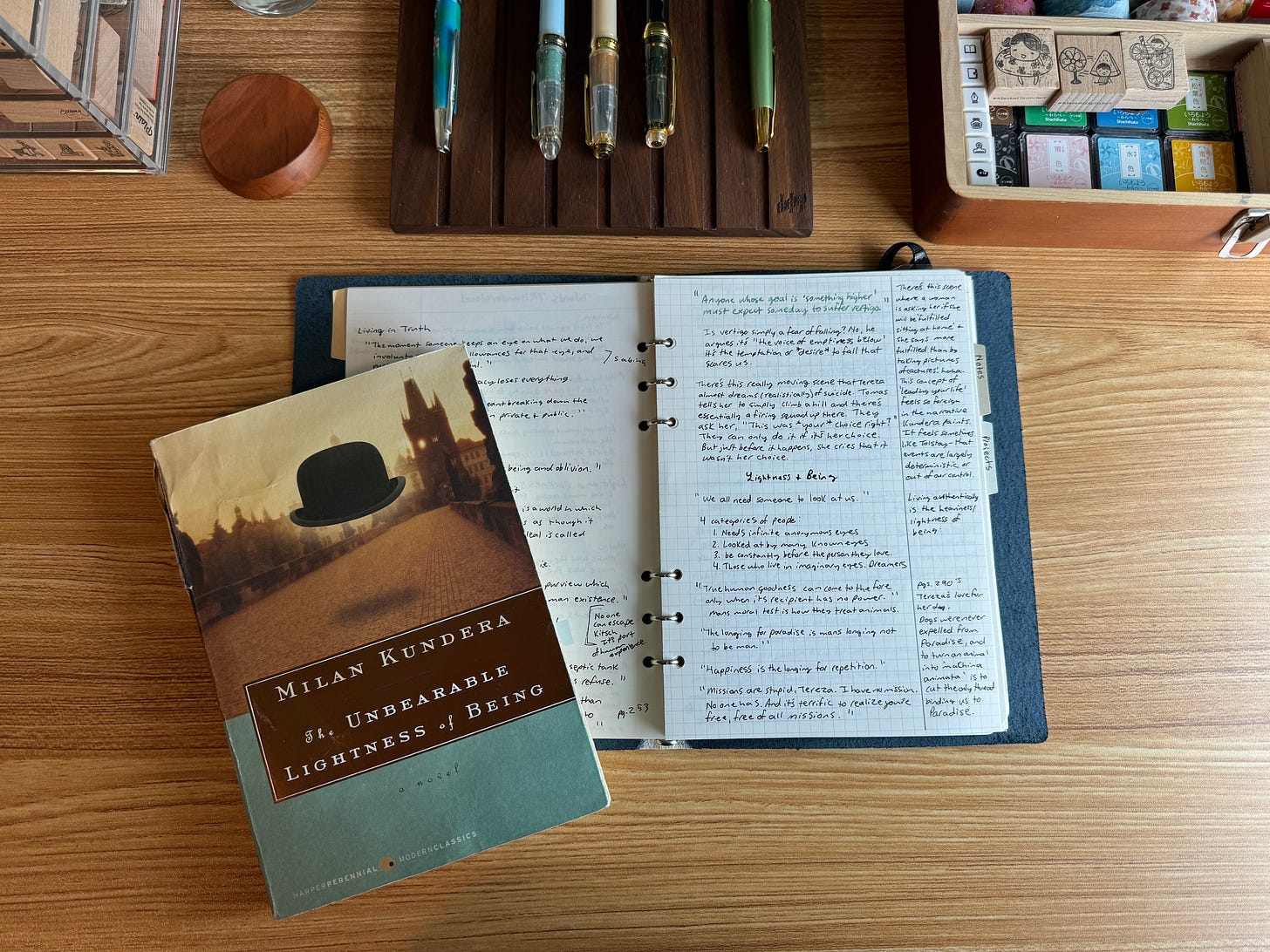

Discussing The Unbearable Lightness of Being By Milan Kundera

Eternal return, living grounded, and social media kitsch

If you’d rather listen than read check out my YouTube video here.

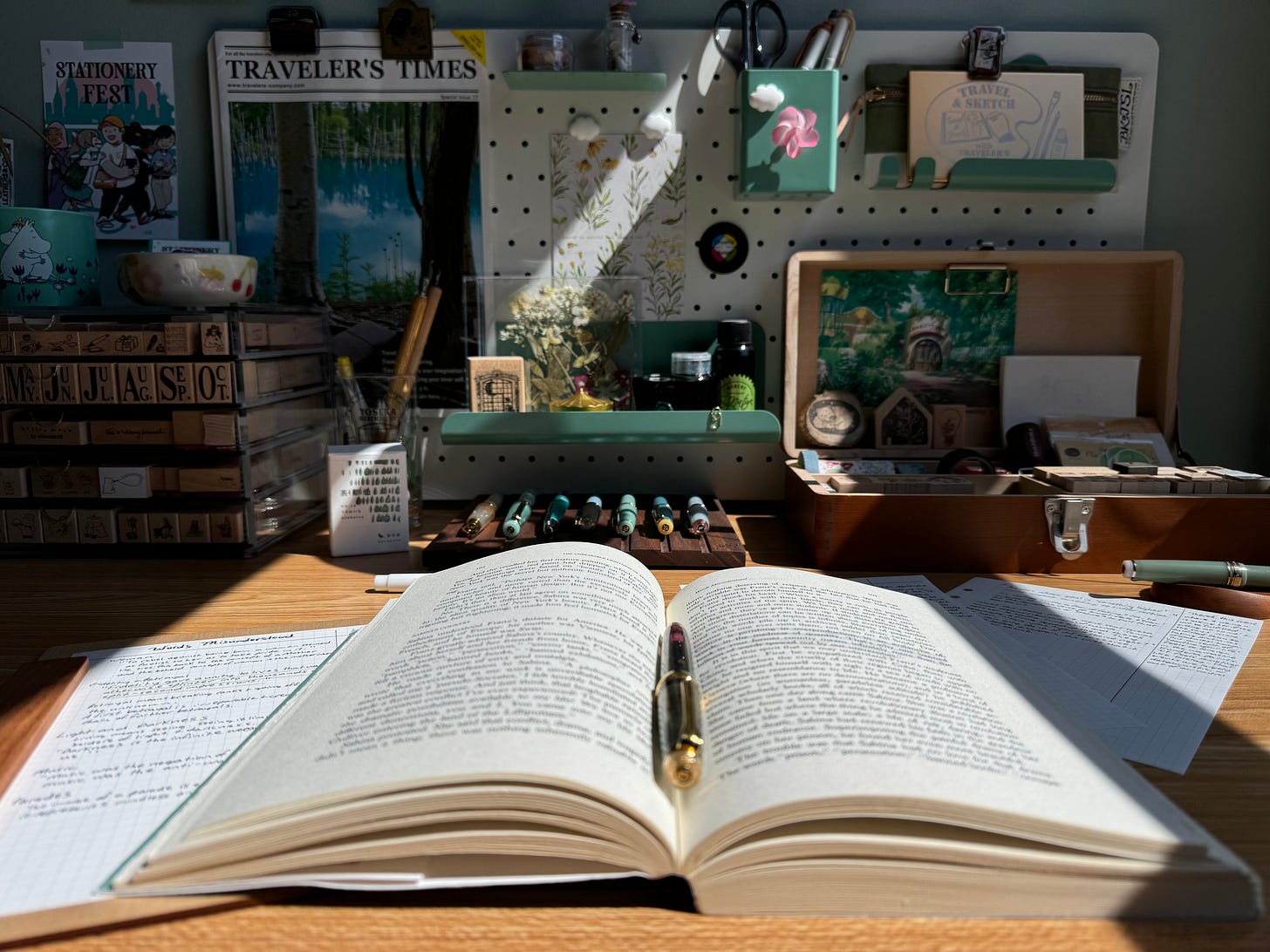

The Unbearable Lightness of Being was published in 1984 by Milan Kundera, a Czechoslovakian novelist. It’s written in the style of philosophical literary fiction, similar to Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea or Tolstoy’s War and Peace. That is to say, it inserts philosophical concepts or assertions in between and within the narrative.

The novel takes place in 1968, during the Prague Spring, when the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. On the surface, the novel is about relationships between men and women and well… a whole lot of sex. Like, really, a lot of sex. But aside from that, it’s a great “how to live” exploration piece.

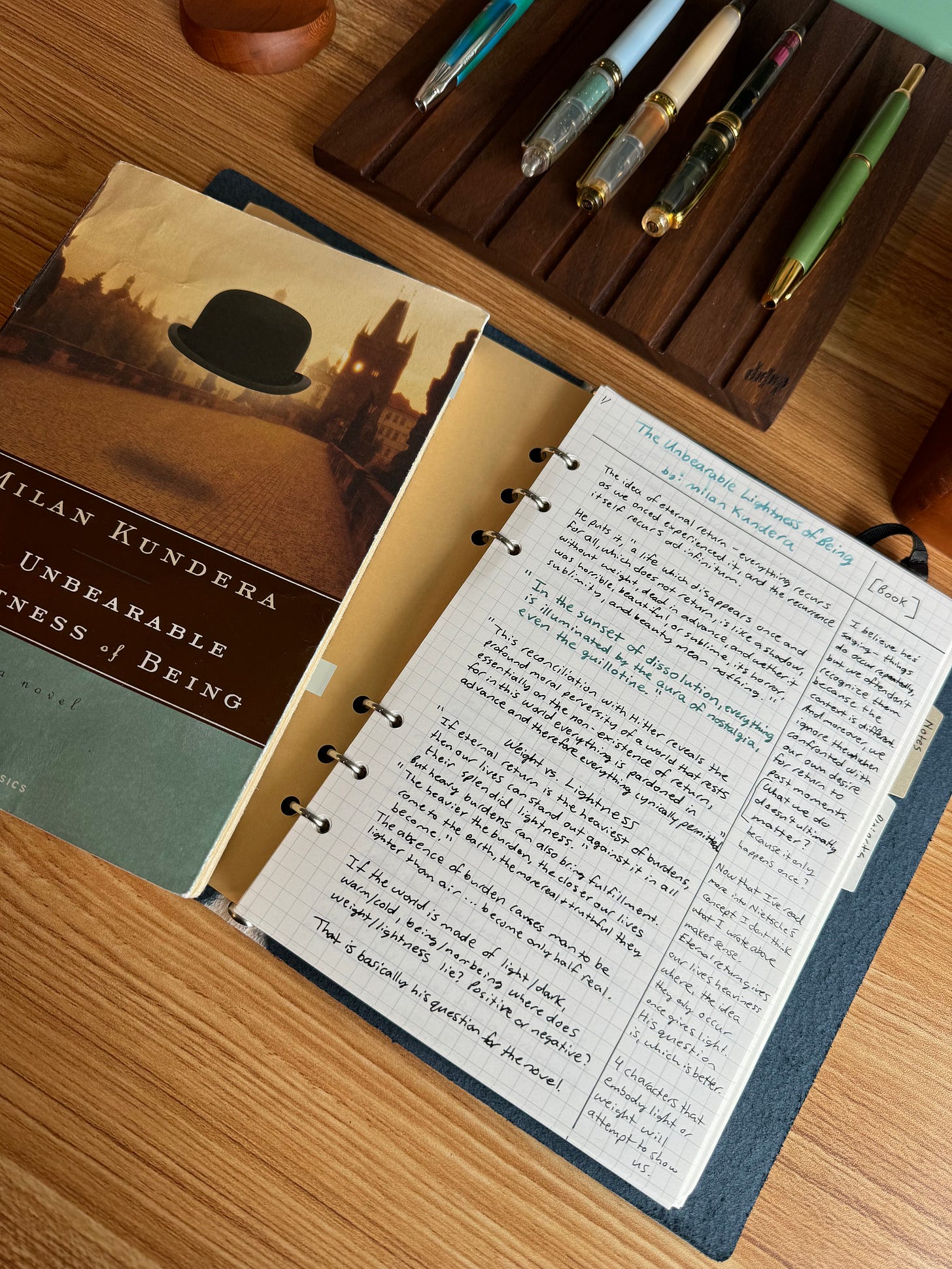

The novel begins with an assertion about a concept called eternal return, which Kundera describes as “the idea of eternal return—everything recurs as we once experienced it, and the recurrence itself recurs ad-infinitum.” Or more simply, time happens in an infinite loop. This topic has been explored in science fiction, but Kundera is pulling this from Existentialism and Nietzsche, which he references in the novel.

So if you’re anything like me (especially as a writer trying to be heard in the world), you’d probably want to close the book at this point thinking, “How did this guy get published?”, “This would have never made it past an agent?”, “Who starts a book this way?”. It’s a bit of a heavy start, but I do think it’s worth wading through and that there’s a reason this is a classic, and classics are classics.

To return to eternal return, I want to take a moment to clarify, eternal return is a thought experiment in philosophy that Nietzsche created to help us explore the meaning of life. There is some sense that Nietzsche considered it more literally for a time, but I want to be clear that Kundera and Nietzsche aren’t asking “is the science/cosmology of eternal return real?”, but rather “if your actions did re-occur infinitely, what meaning would that give your life? How would you choose to live?” This is an important distinction, I think because when I’ve had to read the first few pages several times to really understand them, and my brain kept taking them quite literally (again in a bit of a science fiction mindset).

The reason he starts with this, ahem, weighty introduction, is that he’s going to use his novel as a challenge to the concept. He then connects it to the duality that gives the novel its namesake: lightness and weight.

“The myth of eternal return states that a life which disappears once and for all, which does not return, is like a shadow, without weight, dead in advance, and whether it was horrible, beautiful, or sublime, it’s horror, sublimity, and beauty mean nothing.”

Kundera makes an assertion about the implications of eternal return that our protagonist, Tomas, is also going to embody, which is that: If life only occurs once, it may as well no occur at all and nothing really matters. The realization that we only have one life to life gives us freedom. This is the concept of lightness.

On the other hand, he says, “In the world of eternal return, the weight of unbearable responsibility lies heavy on every move we make.” The idea that our actions will recur again and again gives a heaviness to our lives. This is the concept of weight.

But he gives us warnings for both of these ways of thinking. If heaviness can weigh us down and keep us from living authentically, lightness can make way for nostalgia. A longing for what was but will never be again creates a world where “everything is pardoned in advance and therefore everything is cynically permitted.”

The challenge of lightness is then, that “the absence of burden causes man to be lighter than air… only half real.” Perhaps we shouldn’t be so quick to reject heaviness. For, “The heavier the burden, the closer our lives come to the earth, the more real and truthful they become.” Heavy burdens can bring fulfillment.

His question is, which shall we choose? Is it better to live in lightness or in with weight? To explore that question, he shows us the lives of four characters that represent these dualities.

Tomas and Tereza

The first character introduced is Tomas, a Czech surgeon and also, uh, a womanizer. Thinking that love and sex are two different things, Tomas is the source of many sex scenes throughout the novel. This is one of his ways of living in lightness. But by a series of chances, he crosses paths with Tereza, and he asks himself if he’s experiencing love. This is where Kundera introduces Tomas’ relation to eternal return—uttering the German phrase “Einmal ist keinmal”, meaning “one occurrence is not significant”. This phrase is more often used in the context of mistakes or second chances, but Tomas extrapolates this to life in the context of return.

“And what can life be worth if the first rehearsal for life is life itself.”

Tomas allows him to fall into deterministic thought, thinking that any of his decisions cannot matter because they only happen once and there is no way to compare them to alternatives. But also in the sense that he sees Tereza as an element of fate, imagining her as a child sent down the river to him in a basket.

“A single metaphor can give birth to love.”

In the days she spends ill with the flu in his home, he allows that this ‘single metaphor’ of Tereza is what gave birth to his love for her. He doesn’t turn her away and eventually marries her. The two continue on together, although Tomas does not give up his womanizing (a source of great strife for Tereza). The Russian invasion has them flee from Prague to Zurich, back to Prague and finally to the countryside.

Meanwhile, Tereza is one example of living with weight. Her perspective often deals with embodied experience and a sense of shame surrounding her body that was placed there in childhood by her mother. It’s also interesting that she becomes a photographer, which I associate with the passive, observing body rather than a participating person. Part of her heaviness is in searching for something outside of her body, hating her own.

She goes so far as to leave Tomas behind in Zurich and return to Prague because she believes that she is not strong enough, or her love is not good for Tomas. He, of course, follows her back, and they experience a dance of, can’t live with or without the other.

One of Tereza’s most moving scenes for me is in a confrontation with suicide. Throughout the novel, she struggles with Tomas’ infidelity, and rather than believing he’s wrong for doing it, she considers herself “just not strong enough to stand up to it.” This scene begins very real, as if she is sitting on a park bench with Tomas, but by the end you realize it was a nightmare.

Tereza says that she can’t take it anymore, and Tomas says he has a solution for her and that she’s must walk up to Petrin Hill to find it. What she finds there is essentially a firing squad and a handful of other people who have gone there for the same reason. They ask her if it “was her choice” and afraid of letting Tomas down she hesitantly says yes, but asks to go last. She watches as they blindfold the other men and fire, with no sound. He then offers Tereza a blindfold, which she refuses, saying that she “wants to watch”. At this moment, she realizes she only wants to postpone death, and staring up into a flowering chestnut tree she finally yells, “But it wasn’t my choice!” He says they cannot do it if it wasn’t her choice, saying, “We haven’t the right.” She embraces the tree as if it were “her long-lost father”.

I found this scene so moving because I think it really captures how those feelings of heaviness in life can push people to the edge, looking out at what’s beyond life. Of all four characters, Tereza is the one who does this the most and, perhaps because of this, I find her to be the most interesting character. What happens in this scene builds up what I believe to be the main message of this book. Tereza can’t make the choice to say yes to the firing squad because of all the weight she bears, she bears the one most important. She loves Tomas.

Sabina, Franz, and kitsch

The other characters in this novel are Sabina, who is Tomas’ mistress for most of the novel, and Franz, another lover she is with for part of it. Sabina is lightness, and Franz is heaviness.

There’s a lot we could talk about here between these two, but I want to focus on one element, which is the concept of kitsch. So you may have heard this term applied to art, usually art that is vulgar or in bad taste, and overly sentimental. Kundera is taking this word a little farther (and it's still related) to say that the idea of kitsch is to ignore things that are too gross or too inconvenient to humans. If you think of this in the context of the art style, kitschy art is such that it's the product of miming without original thought, it lacks depth, and often is overly cutesy to evoke sentimentality. In this way, it doesn’t deal with the reality of life.

“The categorical agreement with being is a world in which shit is denied and everyone acts as though it did not exist. This aesthetic ideal is called kitsch.”

He uses the somewhat grotesque (but that’s the point) concept of “shit” to say that kitsch is the absolute denial of bodily excrement. But the more notable part here is the description that everyone acts as though it doesn’t exist. It’s this cultural and social rejection of the topic that ultimately makes kitsch, kitsch.

Moreover, he describes it as, “Kitsch is the stopover between being and oblivion.” Basically, we use kitsch to hide from death.

There’s a scene where Sabina says, “My enemy isn’t communism, it's kitsch!” This concept is further explored in many other scenes where she describes her art, comments on parades, and even brings up American politics (as she winds up living in America at the end). She believes that all these political and ideological movements are the same underneath. That they all employ “kitsch” as a way of controlling or swaying populations through propaganda. Propaganda that attempts to sell paradise to a population who desperately wants to shield themselves from the realities of life and death.

The Unbearable Lightness of Social Media

“Culture is perishing in over production, in an avalanche of words, in the madness of quantity. That’s why one banned book in your former country means infinitely more than the billions of words spewed out by our universities.”

I found some very unexpected thoughts appearing while I read the novel that revolve around social media, which, of course, didn’t exist when Kundera wrote the novel. And yet, there’s some surprisingly prescient lines that, I think, gets at the heart of things that are simply elements of the human condition that are expressed and exasperated by social media.

There’s a section of the book called “Words Misunderstood” where Kundera defines different words in the context of how his characters understand them. One of the words he defines is fidelity. This is not strictly in the romantic sense; it’s defined for Franz in the context of the love he has for his mother. But it’s also contrasted with Sabina and her life of “betrayals” (essentially, moving from person to person and place to place without any lasting attachment). And here we get one of the most telling lines in the novel (in my opinion):

“Fidelity gave a unity to lives that would otherwise splinter into thousands of split-second impressions.”

It struck me how much this line describes our online interactions on social media. When you abandon “fidelity” to the real people in your life, you can constantly “betray” yourself in a shifting tide of personalities, often mimed from the current of trend. And in doing so, you exist only as a “thousand split second impressions” or photos and 10-second videos that either did or did not receive enough views and likes.

And to tie back to Sabina, all these attempts to craft our perfect self online is our way of curtaining off the things about life we would rather not deal with. When photos of the Boston Marathon bombing first appeared on Facebook in 2013, everyone was up in arms to have them removed because it was “too violent” or “too much gore”. But really, it made us uncomfortable. We come there to see pictures of friends and cute puppies, not to be reminded that death is always waiting for us around the corner. Essentially, in the context of Kundera, we come to social media for kitsch.

“The longing for paradise is man's longing not to be man.”

The images that social media creates is one in which you will never age (if you just buy this product), you will be the perfect parent (if you just buy this course), and you will have the perfect romantic relationship (if you just use this dating app). And we eat it up because we long for paradise. We long to live in a world where we can have it all. And social media happily gives us, in an infinite feed, that “folding screen to curtain off death.”

There’s another scene in which Sabina reflects on communist propaganda films, and she shudders at the reality that these films paint as paradise (not dissimilar to Terezas dancing dream sequence). Sabina comes to the conclusion that it’s better to live under communisms current regime than it would be to live under communisms vision for the world. This is the light we need to cast on our social media lives. We need to realize the curtain for what it is—that to live in a world where everyone looks perfect, buys the same products, and regurgitates the same “skibidi toilet” jokes is its own kind of hell. If you’re going to post on social media, post what’s real and post less.

Because kitsch is the lighter fluid that keeps social media burning.

Eternal Return: A mad myth of determinism

In the very first chapter, when Kundera introduces eternal return, he calls it a “mad myth”. I am beginning to see why he calls it such. Ultimately, I think that eternal return doesn’t really give us heaviness or lightness if it were true.

If everything returns in a loop, then what’s going to happen has already happened, which means you have no agency. There’s no real heaviness to your decisions because they’re already made. If life only occurs once, then there’s a chance that we do have free will, that our choices are at least our own. The fact that they “dissolve in the sunset of dissolution” doesn’t mean that they don’t have some impact. If anything, eternal return exacerbates the kitsch concept (and one could read kitsch as a proof of eternal return), which makes life seem more like an endless carnival loop.

We all live in the waxes and wanes, the brightness and shades of lightness and heaviness. No life is either or. Neither is better or worse. We cannot choose to live one without forgoing the other. Lightness is unbearable because we know heaviness is around the corner. But without heaviness we float away as no-one, nothing, not even a moment.

The heaviness of raising a child can give way to the lightness of loving that child for who they are.

The heaviness of loving your spouse through difficult times can give way to the lightness of being loved in return.

Atlas held up the world.

There’s a concept in Japanese culture called ichigo ichie, which focuses on treasuring the present moment as a one-time occurrence. Some translations are “once a meeting” or “in this moment, an opportunity”. More simply, everything occurs only once, therefore everything is beautiful. It’s the only possible version of that moment and will never occur again. This may at first seem to be Kundera’s version of lightness, but what I really think it represents is the middle road of heavy and light.

In the book, lightness is represented more so as “nothing matters” in the case of Sabina’s life of betrayals. The shift in Tomas at the end of the novel is that he realizes that there is one heavy burden worth bearing.

Love is the only heavy burden worth bearing

Does Kundera give an explicit answer to his original question, “is light or weight better?”. Of course not. We’re supposed to derive the answer from looking at how the characters he gave us lived their lives. But I think the scene he chose for his ending is notable, in part because it’s temporally out-of-place (we learn that Tomas and Tereza were killed somewhere in the middle of the novel). But more so because of what he shows us last.

Tomas has finally chosen to love Tereza and only Tereza, but also to cast off his conception of having a “mission for his life”.

“Missions are stupid, Tereza. I have no mission. No one has. And it’s terrific to realize you’re free, free of all missions.”

The novel ends in carefree bliss, Tomas and Tereza dancing at a bar, enjoying their love for each other and friendship with others. This blissful single moment, of which there will never be another just like it. It represents living life with one heavy burden and casting off all the rest.

The only heavy burden worth bearing, and the burden that makes life worth living, is love.

Join the Discussion

Have you read The Unbearable Lightness of Being? How do interpret Kundera’s question of light vs. weight?